One of the most striking ideas in modern psychoanalytic thinking is that even the most extreme psychological states are, at their core, attempts at survival. In the field of modern psychoanalysis this becomes clear in the notion that the schizophrenic reaction is not a fixed, biologically determined fate but an organized defense, one that can be psychologically reversed.

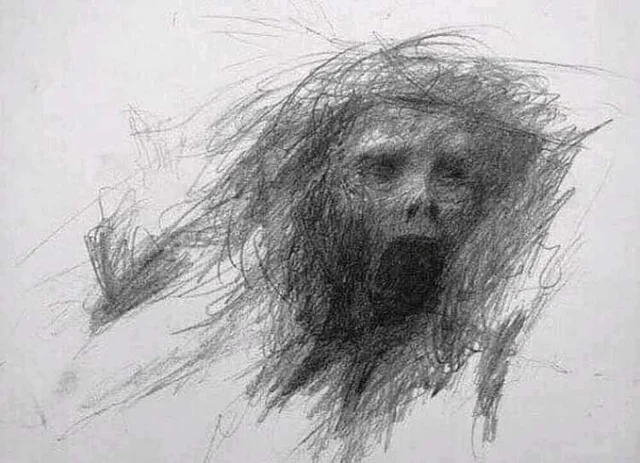

The line from Spotnitz that “the schizophrenic reaction is psychologically reversible, most readily so when the predominant factor is life experience,” carries within it an entire philosophy of the human mind. It suggests that the psyche, even under immense strain, is not simply breaking down but reorganizing itself around unbearable feelings, unmanageable aggression and early relational trauma. The eventual fragmentation of the mind is not so much a chaos but an attempt of the psyche to protect itself when its ordinary capacities have failed.

This reversibility is not magical, nor is it guaranteed. But it gestures toward something profoundly hopeful: that human experience, when it wounds, can also heal; that new forms of emotional contact can soften old defensive structures; that psychosis, in many cases, is not a life sentence but a reaction that emerged in human relationship and may soften again within human relationship.

Spotnitz’s framing of etiology—hereditary, constitutional, environmental—is a reminder that no single pathway leads to psychosis. Sometimes a biological vulnerability is dominant; in other cases, the decisive blow comes from life experience: isolation, trauma, invalidation, or a collapse in early attachments. But what matters most for treatment is not the specific mix of factors but whether the person can be reached through emotional communication, whether the therapeutic situation can offer a different relational experience than the one that precipitated the defensive retreat.

From a contemporary psychoanalytic perspective, what makes the notion of reversibility compelling is not the promise of erasing symptoms but the possibility of reorganizing meaning. If psychosis is a defensive structure, then therapy is not about dismantling it with force but about approaching it with respect. Respecting the space (and the time) needed to unfold the mind fragmentation caused by an excessive force of aggression turned against the self and the mind.

This view asks the therapist to stay close to what feels frightening or impenetrable. It requires a faith not only in the patient’s mind but in the relational field itself: the idea that emotional contact, even at the edges of symbolization, can reach parts of the psyche that words cannot. The reversibility Spotnitz speaks of is, in many ways, the fruit of that faith.

To say that the schizophrenic reaction can be reversed is not to deny suffering but that suffering does not define the limits of possibility. Even in its most disorganised form the mind searches for a way to reconnect. And perhaps that is the deeper meaning behind the claim: not that all fragmentation can be undone, but that the mind, given the right conditions, never stops trying to come home to itself.